Dataset: Instructron Student Learning Profiles | Fall 2025 (Aug-Nov 2025) | Aggregate data across classrooms from teachers who had students complete profiles | Grades 4-8 | All subjects

Anonymization: Aggregate data; paraphrased student language; randomized IDs

What we didn't do: No training on student work; profiles are opt-in and teacher-assigned; responses reflect student self-perception, not performance metrics

The Open Field

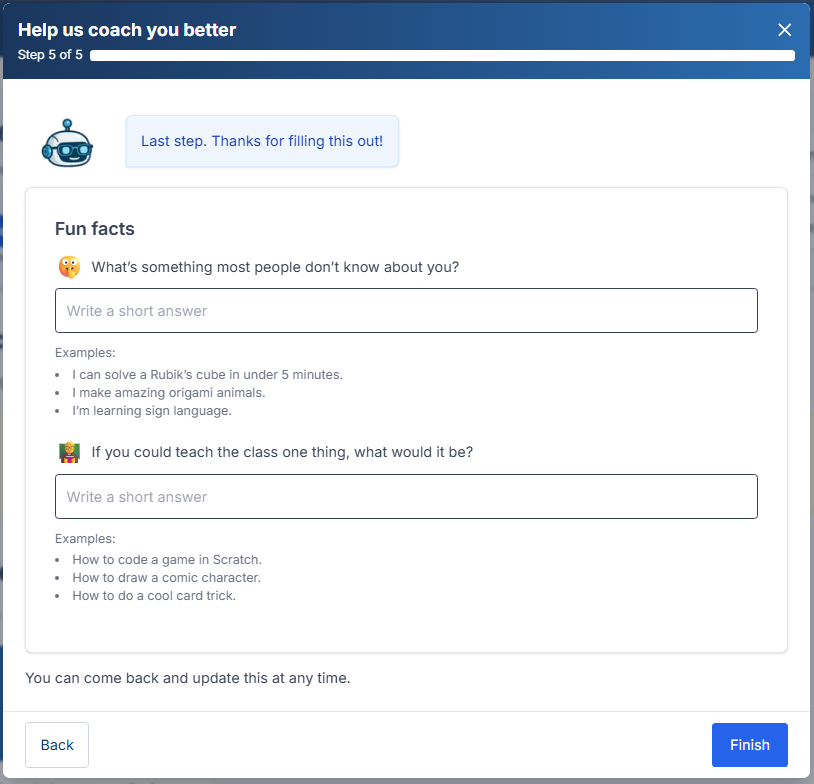

In the final step of their learning profiles, students see two simple text fields:

"What's something most people don't know about you?"

"If you could teach the class one thing, what would it be?"

Below each field, we show a few examples such as "I can solve a Rubik's cube in under 5 minutes" or "How to code a game in Scratch", but the prompts themselves are intentionally open. No multiple-choice options. No required format. Just space to write whatever feels true.

We expected brief responses. Maybe a sentence or two. "I'm good at math" or "I like to read."

What we got was something much richer.

What Students Lead With

When we analyzed responses across Fall 2025 4th-8th grade classrooms, patterns emerged from what students chose to share.

In this sample, roughly one in six students (~16-19%) immediately led with their athletic identity:

"I play travel soccer"

"I'm a gymnast—I can do back handsprings and aerials"

"I do martial arts and I'm working toward my black belt"

"I'm on the basketball team and I practice every day"

Notice the language. Not "I like sports." Not "I'm good at PE."

"I'm an athlete." They defined themselves through movement and competition.

But that wasn't the only pattern. Others wrote:

"I speak Spanish at home with my family"

"I can speak Farsi and English"

"I'm learning Japanese and I know the alphabet"

Some students led with creative identities:

"I love to draw and I'm really good at realistic eyes"

"I write stories and songs in my free time"

"I crochet and make plushies"

And some students revealed challenges:

"I'm shy and need to feel comfortable to talk"

"I have ADHD and sometimes need a lot of help"

"I'm good at reading but math is hard for me"

These weren't answers to specific questions. These were students choosing what to reveal about themselves when given complete freedom. And those choices—what students lead with, what they claim as identity, what they name as challenges—tell us something powerful about how they see themselves as learners.

The Private Space

There's something important about how students share this information. Unlike a class discussion or public sharing, the profile is private—completed individually, teacher-only by default. For some students, especially those who are shy, anxious, or hesitant to speak up in front of peers, this private space removes the pressure of performing for an audience.

A student who might never raise their hand to say "I speak Spanish at home" can write it freely. A student who feels vulnerable sharing "I have ADHD" doesn't have to worry about peer reactions. A student who's proud of their athletic achievements but doesn't want to seem like they're bragging can claim that identity without the social dynamics of a classroom.

This isn't to say public sharing isn't valuable—it absolutely is. But the private profile creates a different kind of opening, especially for students who need that safety to be fully themselves. When students know their responses go directly to their teacher (and stay private unless they choose otherwise), they're more likely to be honest, vulnerable, and complete.

Five Identity Patterns

When we analyzed the open-ended responses across classrooms, five clear identity patterns emerged:

1. Athletic Identity (16-19% of Responses)

About one in six students immediately identified themselves through sports: travel teams, specific positions, skills they're working on, hours of practice.

What it tells us: These students understand practice, feedback, incremental improvement, and performing under pressure. They know what "getting better" feels like because they experience it every week at practice.

How to honor it: Use sports contexts in math (calculating stats, graphing performance), writing (game narratives, persuasive essays about sports rules), and speaking (explain your sport's strategy to someone who's never played).

2. Multilingual/Cultural Identity (About 5% of Responses)

Students mentioned speaking Spanish, Farsi, Vietnamese, German, Japanese, Korean, Latvian at home. Some mentioned cultural traditions, heritage foods, or family customs.

What it tells us: These students navigate multiple linguistic and cultural contexts daily—a sophisticated cognitive skill. They're natural translators and cultural bridges.

How to honor it: Invite them to teach vocabulary or phrases, ask them to explain cultural traditions as informational writing, recognize code-switching as an asset (not a deficit), create space for languages in writing drafts.

3. Creative/Maker Identity (Frequent Mentions)

Students described themselves through making: drawing, origami, crochet, building cardboard models, video editing, creating board games, writing stories.

What it tells us: These students think in projects and tangible outcomes. They understand iterative creation—make something, see what works, revise, make it better.

How to honor it: Offer choice in how students demonstrate understanding (create a model, design a poster, build a prototype), value visual thinking, connect writing to design thinking.

4. Reading/Writing Identity (4-6% of Responses)

Some students led with "I love to read," "I write stories in my free time," "I'm really good at writing," "I know a lot about books."

What it tells us: These students already see themselves as literate—reading and writing are part of their identity, not just school tasks. They're your peer models for reluctant readers/writers.

How to honor it: Ask them to recommend books, invite them to share their writing, have them explain their writing process to peers, create book clubs or writing groups led by these students.

5. Vulnerability and Self-Advocacy (Varied Frequency)

Students disclosed challenges: shyness, stage fright, ADHD, autism, tics, specific subject struggles ("math is hard for me"), need for support ("sometimes I need a lot of help").

What it tells us: These students are self-aware and willing to advocate for their needs when they feel safe. This self-disclosure is a trust signal—they believe telling you this will lead to support, not judgment.

How to honor it: Provide the accommodations they're asking for (sentence frames for shy students, visible steps for ADHD, choice in format for anxiety), normalize struggle ("everyone finds something challenging"), create low-stakes practice environments.

Why This Matters: Identity-Informed Teaching Isn't Just Nice—It's Effective

Recognition of student identity isn't about being nice or making students feel good (though those matter). It's about leveraging what students already know and care about to strengthen academic learning.

1. Identity Anchors Reduce Stereotype Threat

When students see their identities reflected positively in academic contexts, stereotype threat decreases. Stereotype threat—the anxiety that you'll confirm negative stereotypes about your group—impairs performance, particularly for students from marginalized groups (Steele & Aronson, 1995; lab experiments; college samples; strong internal validity; effects vary by context).

Naming and honoring student identities (athletic, multilingual, creative) signals: "Your full self belongs here."

2. Expertise Transfer: Skills From One Domain Apply to Another

A student who practices gymnastics 10 hours a week understands feedback, incremental improvement, and deliberate practice better than most adults. When you explicitly connect their athletic experience to academic learning—"You know how your coach gives you one thing to fix each week? That's exactly how we'll approach your writing revisions"—you help them transfer expertise across domains.

3. Interest + Identity = Sustained Engagement

Interest alone is situational ("This animal problem is cool"). Identity is enduring ("I AM someone who cares about animals"). When students' interests align with their identities, engagement becomes self-sustaining. They don't need external motivation—it's part of who they are (Hidi & Renninger, 2006; theoretical review; widely used framework; K-12 and higher ed).

How Instructron Supports This: From Identity to Action

The identity patterns we discovered—athletic identity, multilingual identity, creative identity—aren't just interesting data points. They're opportunities to honor who students are and connect their expertise to academic learning.

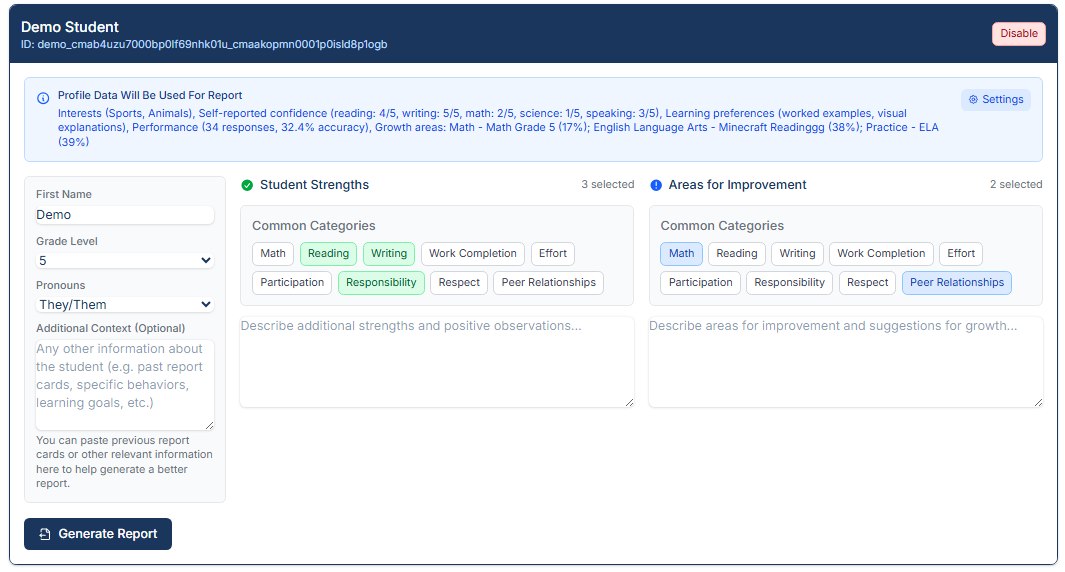

Teachers can encourage their students to complete learning profiles—a quick 5-step process that captures how students see themselves. What seems like a simple form actually gets leveraged across the platform in ways that honor student identity and signal: "Your full self belongs here."

Quick highlight of the full Student Profile flow.

Risks & Guardrails

- Identity ≠ destiny: Offer choice; never force alignment. Students should always be able to opt out or change their responses.

- Privacy by default: Fun facts are teacher-only unless explicitly shared. Profile data is never automatically surfaced to peers or AI without teacher choice.

- Stereotyping risk: Recognize identity signals without assuming they define a student's capabilities or interests. A student who identifies as an athlete might also love reading—honor the full person.

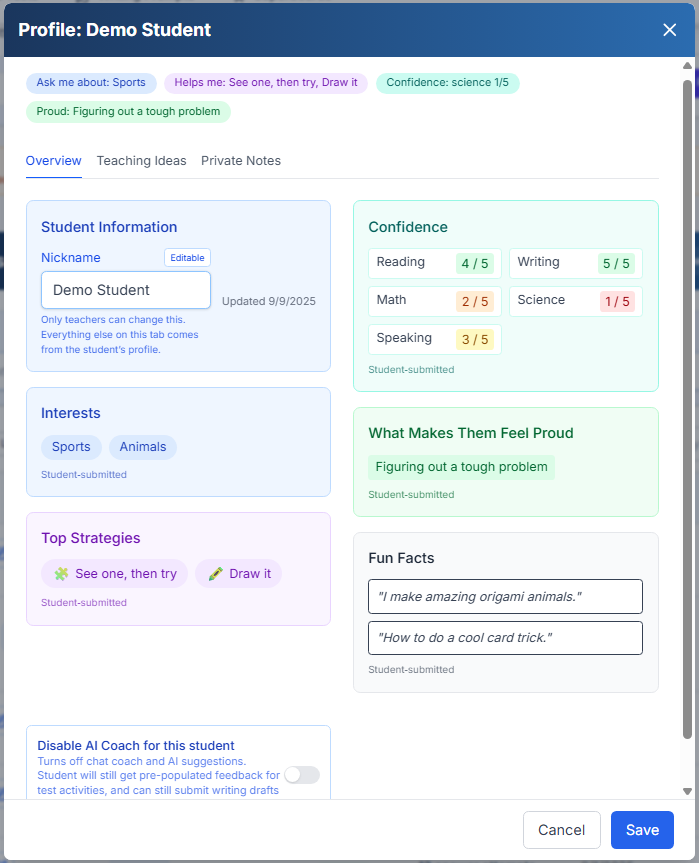

Student Profiles capture three types of identity data—and teachers control all of it:

1. Interests (Student-Selected, Teacher-Visible)

Students select from 14 interest categories: animals, sports, music, gaming, art, nature, helping others, stories/books, cooking, building/making, fashion/design, space, coding, cars.

Teachers see aggregate data for their classroom: "68% of your students chose animals; 55% chose gaming; 62% chose sports.

2. Learning Preferences (Student-Selected, Teacher-Visible)

Students choose up to 3 learning strategies from 6 options: teach a friend, write it in my words, quick quizzes, see one then try, little hint, or draw it.

Teachers see which strategies students prefer—and can use this to pair students, adapt instruction, and understand how their class learns best.

3. Fun Facts (Open-Ended, Teacher-Only)

Students write freely about what they're good at, what they're working on, what they want teachers to know. These responses are teacher-only by default—never surfaced to peers or AI without explicit teacher choice. Teachers can optionally include these insights in report cards, but they're never automatically shared with AI coaching systems.

Privacy by default: Fun facts are teacher-only unless explicitly shared. This ensures students can be vulnerable and honest without worrying about peer reactions or automated systems.

What teachers see:

- Athletic identities: "I play travel soccer," "I'm a gymnast"

- Linguistic identities: "I speak Spanish at home," "I'm learning Japanese"

- Creative identities: "I draw," "I write stories," "I make things"

- Learning needs: "I'm shy," "I have ADHD," "Math is hard for me"

Dynamic AI Adaptation: When Identity Meets Learning Support

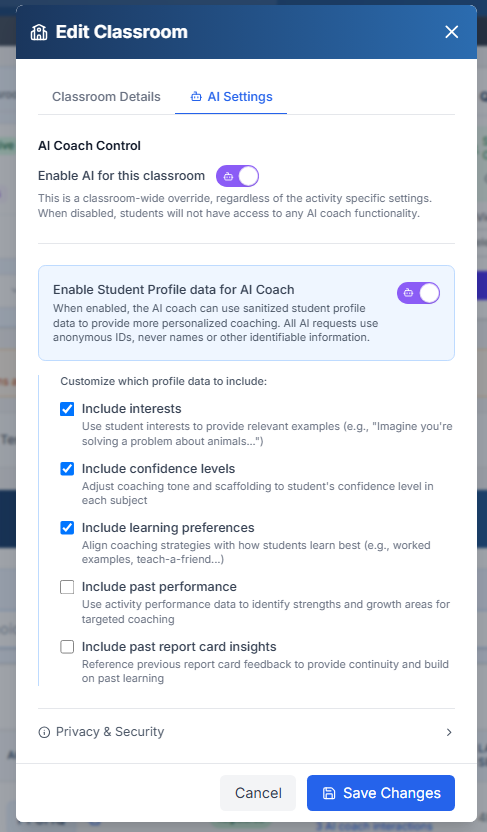

Remember the research on identity and motivation? When students see their identities reflected in academic contexts, engagement increases. The AI Coach can honor this—but only when teachers choose to enable it.

Teachers have granular control over how student profile data shapes AI Coach interactions. In classroom AI settings, teachers can enable or disable specific data types:

- Interests: When enabled, AI Coach uses student interests in examples (e.g., "calculating how fast a cheetah runs" for a student who selected animals)

- Confidence Levels: AI adjusts tone and scaffolding based on self-reported confidence in each subject

- Learning Preferences: Coaching strategies align with how students learn best (e.g., worked examples, teach-a-friend, quick quizzes)

- Past Performance: AI references activity performance data to identify strengths and growth areas

- Report Card Insights: AI can reference previous report card feedback for continuity

Why this matters for identity: When a student who identifies as an athlete sees a math example about basketball statistics, they're not just solving a problem—they're seeing their identity reflected in academic work. This connection strengthens their belief that "school is for people like me."

Example: If a student selected "animals" as an interest, when Coach needs an example for a math concept, it might use "calculating how fast a cheetah runs" instead of generic examples. If they selected "gaming," examples might reference game scores, win rates, or level progression.

Teachers see this happen: Every AI interaction is logged and visible—teachers can see exactly what data was used and whether it helped.

This isn't hidden personalization. It's transparent adaptation that teachers control and can audit at the classroom level, with granular toggles for each data type. The goal: honor student identity while maintaining rigorous instruction.

Four Ways Teachers Are Using This Data Right Now

1. Student Profiles Classroom Snapshot

These aren't just preferences—they're identity signals. When teachers see that most of their class identifies with sports, they're seeing a classroom full of students who understand practice, feedback, and incremental improvement.

Action: "I'm teaching fractions next week. I'll create one animal-themed problem set and one gaming-themed problem set to cover most of my students' interests."

This isn't about making math "fun." It's about recognizing that students who identify as athletes or gamers bring expertise from those domains—and connecting that expertise to academic learning signals: "Your identity belongs here."

2. Expert Spotlighting

Teachers use identity markers to create teaching opportunities:

- Student who speaks Spanish → invited to teach counting, days of the week, cultural context

- Student who "writes stories in free time" → asked to share revision strategies with peers

- Student who does martial arts → asked to explain how they learn new forms (connects to academic practice strategies)

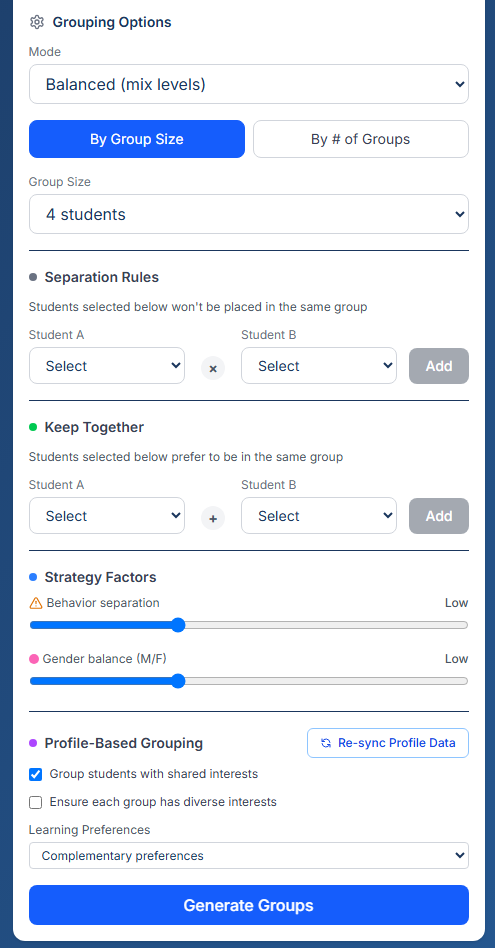

3. Group Generator With Identity Filters

Remember the funds of knowledge research? Every student enters your classroom with expertise. The group generator helps teachers honor that expertise through intentional grouping:

- Group by similar interests: "Create 4 groups of students who all chose sports" (shared context for a sports-statistics project—students see their athletic identity reflected)

- Group by diverse interests: "Create groups with one animal-lover, one athlete, one gamer, one reader" (multiple perspectives for a complex task—each student's identity brings unique expertise)

- Group by learning preferences: Pair students who prefer "teach a friend" with those who prefer "little hint" (complementary learning styles—honors how each student learns best)

- Random with constraints: "Random groups, but no group should be all one interest" (ensures diversity—no student's identity gets isolated)

This isn't just convenience—it's intentional design that helps teachers honor student identity in grouping decisions without manual work. When students see their interests and preferences shape how they're grouped, they're seeing their identity valued in academic spaces.

4. Report Card Generation: Identity-Informed Feedback

Remember those identity patterns we discovered? About one in six students lead with athletic identity. About 5% mention speaking another language. Many claim creative or maker identities. These aren't just interesting facts—they're how students see themselves.

When generating report cards, teachers can include student profile data to create reports that recognize these identities. Instead of generic feedback, reports can acknowledge who students are through interest-referenced examples (e.g., "Emma's interest in animals shines through in her science work..."), confidence-aware language based on self-reported levels, learning preference recognition, and performance context from actual activity data.

This isn't about adding fluff. It's about signaling to students (and parents) that their identity matters—that being an athlete, speaking Spanish at home, or loving to draw isn't separate from their academic work. It's part of who they are as learners.

Teachers see a preview of what profile data will be included for each student before generating reports. Profile data is always optional and teacher-controlled—teachers can toggle it on or off universally, ensuring privacy and flexibility.

5. The Little Things That Make It Feel Special

When students finish their profiles, we celebrate with confetti—but not just any confetti. The confetti uses the emoji icons from the interests they selected. If a student chose animals, sports, and gaming, they see 🐶🏀🕹️ raining down. It's a small detail, but it signals: "We see you. What you care about matters."

In a future post, we'll showcase some additional things we're doing here.

These moments of recognition—from the private space to share, to the personalized celebration, to the ways their preferences shape their learning experience—add up. They tell students: "You're not just a name on a roster. You're a person with interests, preferences, and expertise. And we're going to honor that."

Looking Ahead

The identity patterns we discovered—athletic identity, multilingual identity, creative identity—point to deeper opportunities. We're building more ways to honor these identities:

- Interest-based problem generators: Create multiple versions of the same skill using students' top interests (so an athlete and a gamer both see their identity reflected, even when learning the same concept)

- Writing prompt filters: Match student interests to appropriate prompts (so a student who identifies as a maker can write about building, while a student who identifies as an athlete can write about competition)

- Enhanced visual dashboards: Help teachers see identity clusters and expertise areas at a glance (so teachers can quickly identify which students share identity markers and leverage that for grouping and instruction)

- Deeper analytics: Show how profile data usage correlates with student engagement and growth (measuring whether honoring identity actually increases belonging and achievement)

The goal isn't to replace rigorous instruction with "fun" contexts. It's to recognize the expertise students already have, connect it to what they're learning, and help them see themselves as capable learners because of who they are, not despite it. When students see their identities reflected in academic work, they're more likely to believe: "School is for people like me."

The Research: Why Identity Matters for Learning

Decades of research on motivation, belonging, and culturally responsive teaching reveal a consistent truth: when students feel their identities are recognized and valued in academic spaces, engagement and achievement increase.

Findings are context-dependent; we cite primary sources and report classroom observations, not universal effects.

Belonging and Academic Motivation

Walton and Cohen (2011) demonstrated that even brief interventions affirming students' sense of belonging significantly improved academic outcomes, particularly for students from marginalized groups (field experiment; college; effects strongest for minoritized students).

The mechanism: When students feel they belong in a learning environment—when they see themselves reflected in content, when their expertise is recognized, when their challenges are met with support—they're more likely to persist through difficulty and less likely to interpret setbacks as evidence they don't belong.

When a student tells us "I speak Spanish at home" or "I'm a gymnast" or "I love to draw," they're offering us an identity anchor—something that matters to them, something that defines how they see themselves. Recognizing and honoring those anchors builds belonging.

Funds of Knowledge

Moll, Amanti, Neff, and González (1992) introduced the concept of "funds of knowledge"—the skills, knowledge, and experiences students bring from their homes and communities (ethnographic work; K-12 communities; culturally responsive framework).

The core insight: every student enters your classroom with expertise. A student who speaks Farsi at home has linguistic knowledge. A student who helps care for younger siblings has teaching experience. A student who plays competitive soccer understands practice, feedback, and incremental improvement.

When we tap these funds of knowledge—when we say "You speak Spanish? Can you teach us how to count to 10?" or "You do gymnastics? Can you explain how you learned a back handspring?"—we're signaling that their out-of-school expertise has value in academic spaces.

Identity and Motivation: The Connection Can Be Causal in Field Experiments

Research on identity and academic motivation shows that students who see connections between their personal identities and academic content show higher intrinsic motivation and deeper engagement (Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2009; randomized classroom study; high school science; utility value interventions). Context matters; effects are strongest when tasks remain rigorous and supports are explicit.

When a math problem involves calculating shooting percentages for basketball players, a student who identifies as an athlete doesn't just find it "more interesting"—they see their identity reflected in academic work. This connection strengthens their belief that "school is for people like me."

Try This Today: Identity-Informed Instruction

You don't need a platform or complex systems to honor student identity. Here are classroom-ready strategies:

1. Day-1 "Expert Card" (5 Minutes)

Give students an index card. Ask three questions:

- "What do you spend time on outside of school?"

- "What's something you're working to get better at?"

- "What's something you could teach someone else?"

File these. Reference them when planning lessons, forming groups, or looking for student experts to spotlight.

What to look for: Students who don't fill it out (follow up privately—they may need examples or reassurance it's safe to share), students who reveal expertise you'd never have guessed, patterns across your class (lots of athletes? Lots of gamers? Lots of readers?).

2. Identity-Informed Problem Contexts

When you know you have students who identify as athletes, gamers, artists, or makers, weave those identities into problem contexts:

- For athletes: "A basketball player shoots 40 times and makes 28 baskets. What's their shooting percentage?"

- For multilingual students: "If you know 50 words in Spanish and learn 5 new words each week, how many weeks until you know 100?"

- For makers: "You're building a cardboard castle that needs to be twice as tall. The current height is 15 inches. What will the new height be?"

What to look for: Students engaging more deeply with problems that reflect their identities, students adding extra details from their expertise ("Actually, in basketball you'd calculate field goal percentage, not just shooting percentage").

3. "Class Expert Wall"

Post student-volunteered expertise where everyone can see it:

- Sports Experts: [Student names] → Ask them about practice, competition, teamwork

- Language Experts: [Student names] → Ask them to teach phrases, explain cultural context

- Creative Experts: [Student names] → Ask them about making, revising, finishing projects

When you teach a concept that connects to their expertise, call on them: "Maya, you do gymnastics—how does your coach help you learn a new skill? Is it kind of like how we're breaking down this math problem?"

What to look for: Students recognizing their out-of-school expertise has academic value, students consulting each other (not just you), academic vocabulary spreading ("Oh, that's like when we practice drills in soccer").

4. Normalize Vulnerability Through Identity

When students disclose challenges—shyness, learning differences, subject struggles—honor those disclosures with appropriate support:

- For shy students: Offer pair-talk before whole-class discussion; sentence frames for structure

- For ADHD disclosures: Break tasks into smaller chunks with visible checkpoints; immediate feedback

- For "math is hard" statements: Normalize struggle; connect to their areas of strength ("You're amazing at art—let's use that visual thinking for math")

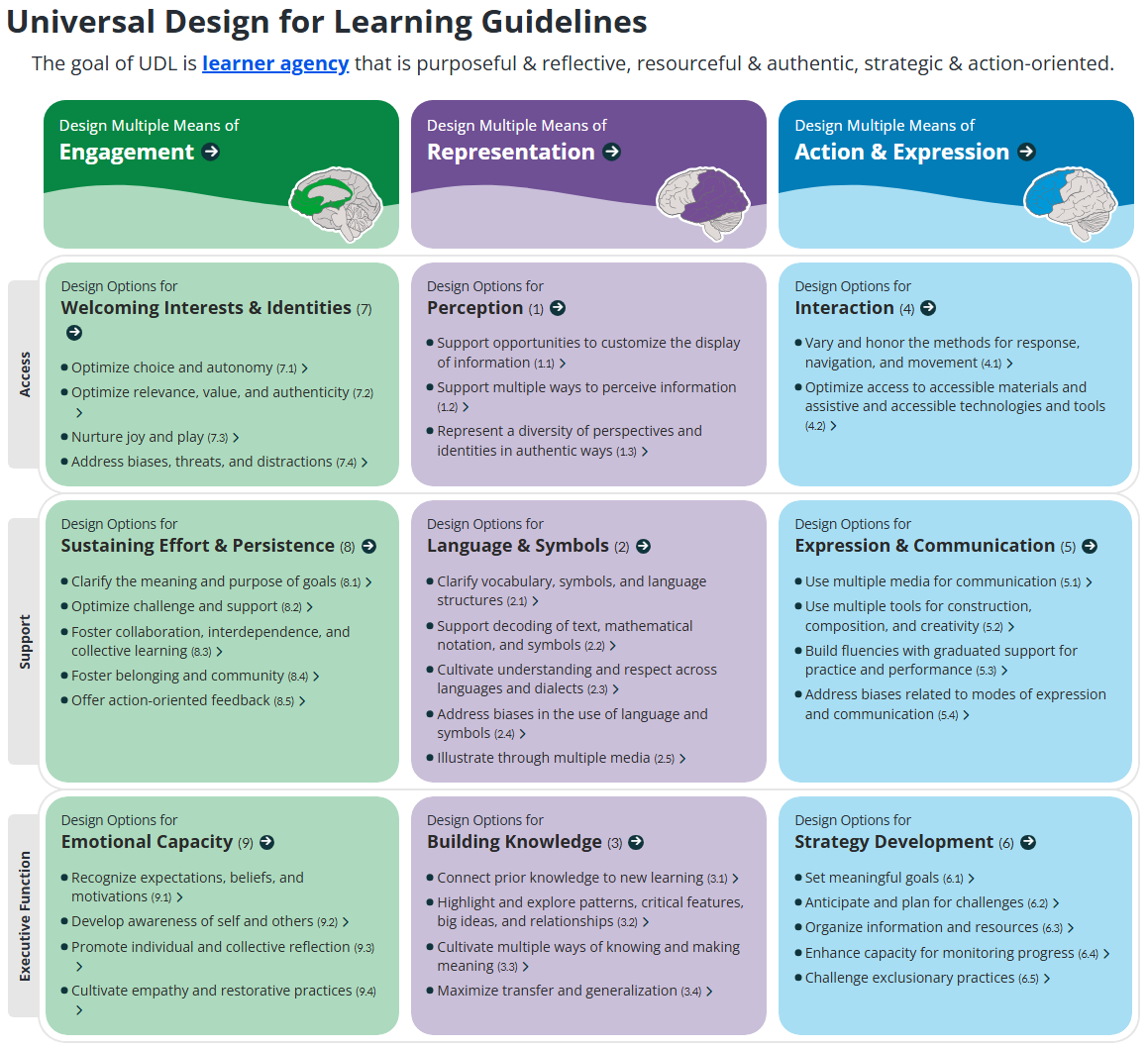

UDL alignment: Our approach aligns with Universal Design for Learning (CAST, UDL Guidelines v3.0) across all three principles:

- Multiple Means of Engagement (Guidelines 7-9): Student interests and identities are welcomed and honored (7.1-7.2); learning preferences sustain effort through optimized challenge and support (8.2); fun facts create space for emotional capacity and self-awareness (9.1-9.2).

- Multiple Means of Representation (Guidelines 1-3): AI Coach uses student interests to represent information in diverse ways (1.3); supports multiple languages and dialects through identity recognition (2.3); connects prior knowledge (athletic expertise, linguistic knowledge) to new learning (3.1).

- Multiple Means of Action & Expression (Guidelines 4-6): Learning preferences recognize multiple expression modes—oral explanation (teach-a-friend), written summary, visual diagrams (draw it), or bilingual responses. These preferences inform how teachers can offer multiple response options and how AI Coach adapts its approach (5.1-5.2). Learning preferences also support strategy development and goal-setting (6.1-6.2).

In the classroom: Teachers can offer students multiple ways to show understanding—mini-demo, sketch, oral explanation, or bilingual response—matching their identity strengths and preferred learning strategies. The platform's learning preferences help teachers know which modes to offer.

Working toward stronger alignment: We're actively building tools to match the learning preferences students select. Students who prefer "teach a friend" will soon be able to speak their responses to the AI Coach. Those who prefer "draw it" will have an integrated drawing tool. Voice input, visual response options, and bilingual response support are in development—because honoring identity means honoring how students express themselves, not just what they express.

What to look for: Students asking for the supports they need, reduction in avoidance behavior, students recognizing that everyone has strengths and challenges.

What Success Looks Like

Watch for these signals that identity-informed teaching is working:

- Students volunteering information about their identities during lessons ("I know about that!")

- Students connecting academic content to their out-of-school lives without prompting

- Students teaching each other based on their expertise areas

- Students who initially said "I don't know" or showed reluctance now claiming expertise in something

- Increased engagement on identity-aligned activities (measured by completion rates, time-on-task, depth of work)

Measure It: Tracking Identity-Informed Teaching

To know whether identity-informed moves are working, track:

- Completion rate on identity-aligned tasks vs. neutral tasks: Are students more likely to complete work when their identity is reflected?

- Identity mentions per week: How often do students volunteer information about their identities during class discourse?

- Expert moves: Count instances where peers ask an identified expert a question or consult them for help

- Interest coverage rate: What percentage of students receive 2+ identity-aligned contexts offered weekly?

These metrics help you see whether honoring identity actually increases belonging and engagement—not just whether students "like" the activities.

Key Takeaways

- For Teachers: About 1 in 6 students lead with athletic identity; about 1 in 20 mention speaking another language; many claim creative or maker identities. Treat these as expertise—not just interests—and reference them in examples, grouping, and feedback to build belonging and engagement.

- For Students: What you do outside school is expertise. Being an athlete teaches you about practice and feedback. Speaking another language makes you a linguistic expert. Making art teaches you about revision. These skills transfer to academic work—if teachers know to make those connections.

- For Learning Design: Identity-informed instruction isn't about pandering or lowering expectations. It's about recognizing expertise students already have and using it as a bridge to new learning. When students see their identities valued in academic contexts, belonging and motivation increase.

- For Belonging: When students choose what to tell us about themselves—and we honor those choices by referencing their expertise, using identity-aligned contexts, and creating space for their full selves—we signal: "You belong here. Your identity is an asset, not something to leave at the door."

Try Today: Review your Day-1 student surveys or profiles. Pick three students whose identities you haven't explicitly referenced in lessons. Find one way to connect each student's identity to academic content today. Watch what happens when students hear: "You're a gymnast—you already know how feedback and practice work. Let's use that same approach for your writing."

Privacy Note: This analysis uses aggregate data from student learning profiles. We paraphrase student responses and remove identifying details. "Fun facts" responses are teacher-only and never shared with AI or other students without explicit teacher choice. Instructron never sends student names to AI systems; interactions use randomized IDs. Teachers have full visibility and control over all identity data through granular classroom AI settings—they can enable or disable interests, confidence levels, learning preferences, past performance, and report card insights independently. Profile data inclusion in report cards is always optional and teacher-controlled. We never train on student work.

References

CAST. (2024). UDL Guidelines version 3.0. CAST. https://udlguidelines.cast.org/

Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111--127. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4

Hulleman, C. S., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2009). Promoting interest and performance in high school science classes. Science, 326(5958), 1410--1412. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1177067

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & González, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Into Practice, 31(2), 132--141. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849209543534

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 797--811. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.797

Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2011). A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science, 331(6023), 1447--1451. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1198364